Helvécia

Le livre sur Helvécia a été shortlisted par le Kraszna-Krausz 2023 Photography Book Award, et ce projet a remporté le 2ème prix du Swiss Press Photo Award 2023, dans la catégorie "Histoires Suisses".

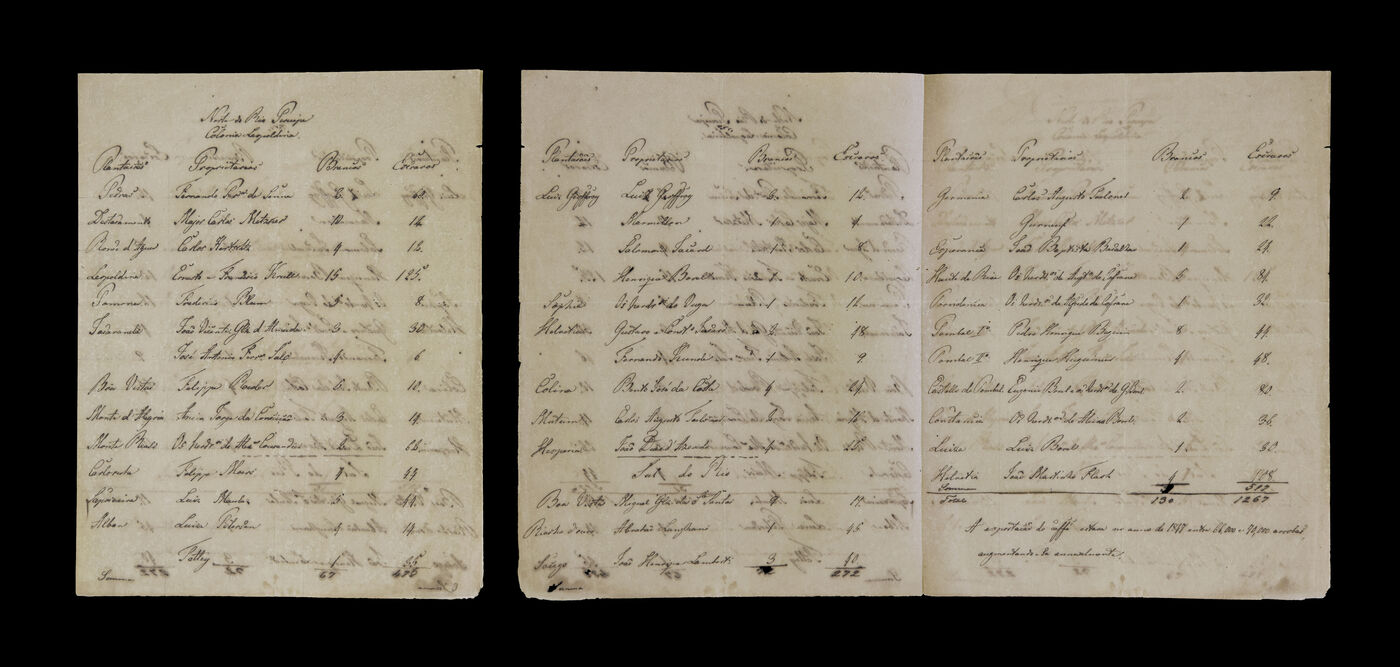

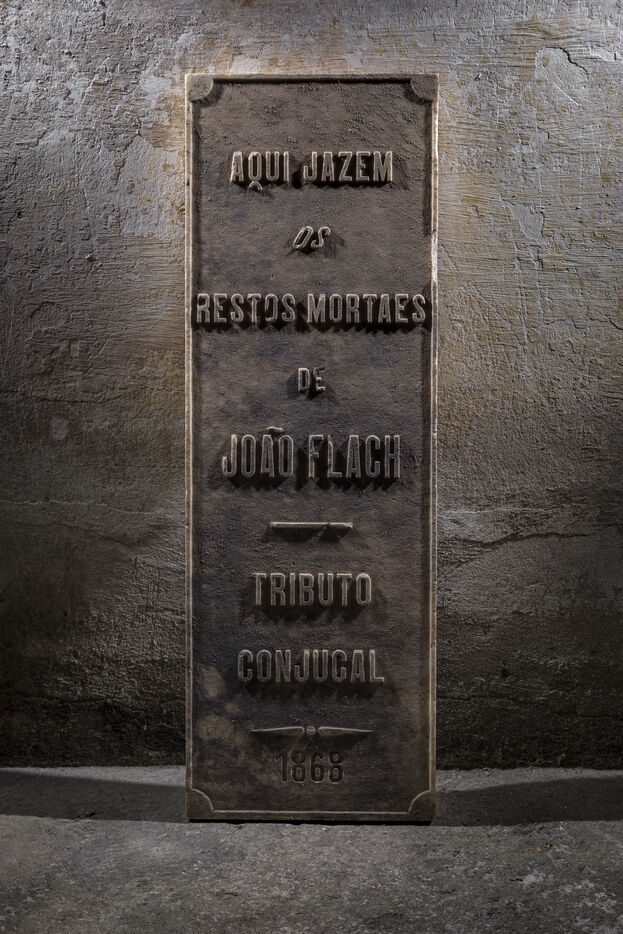

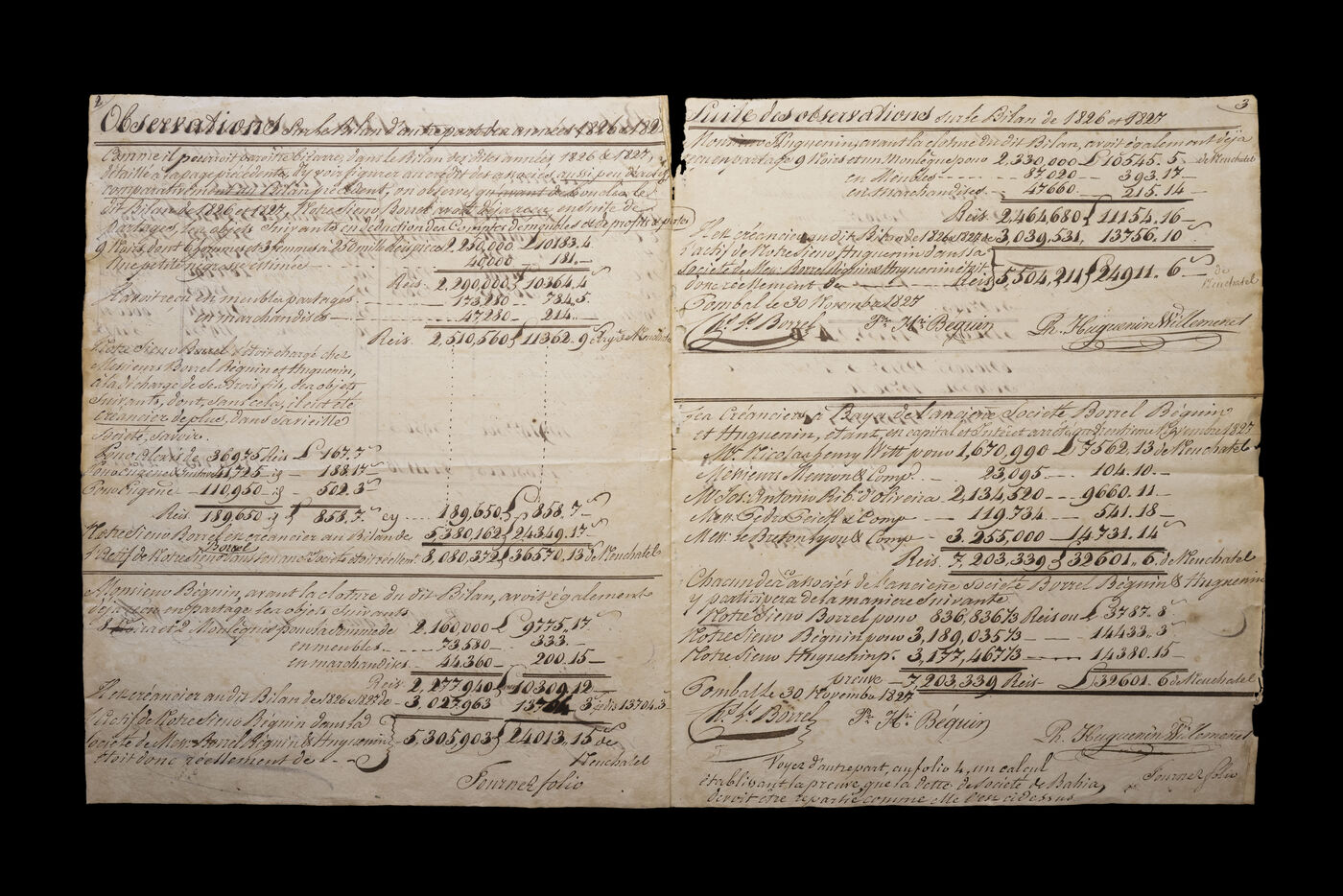

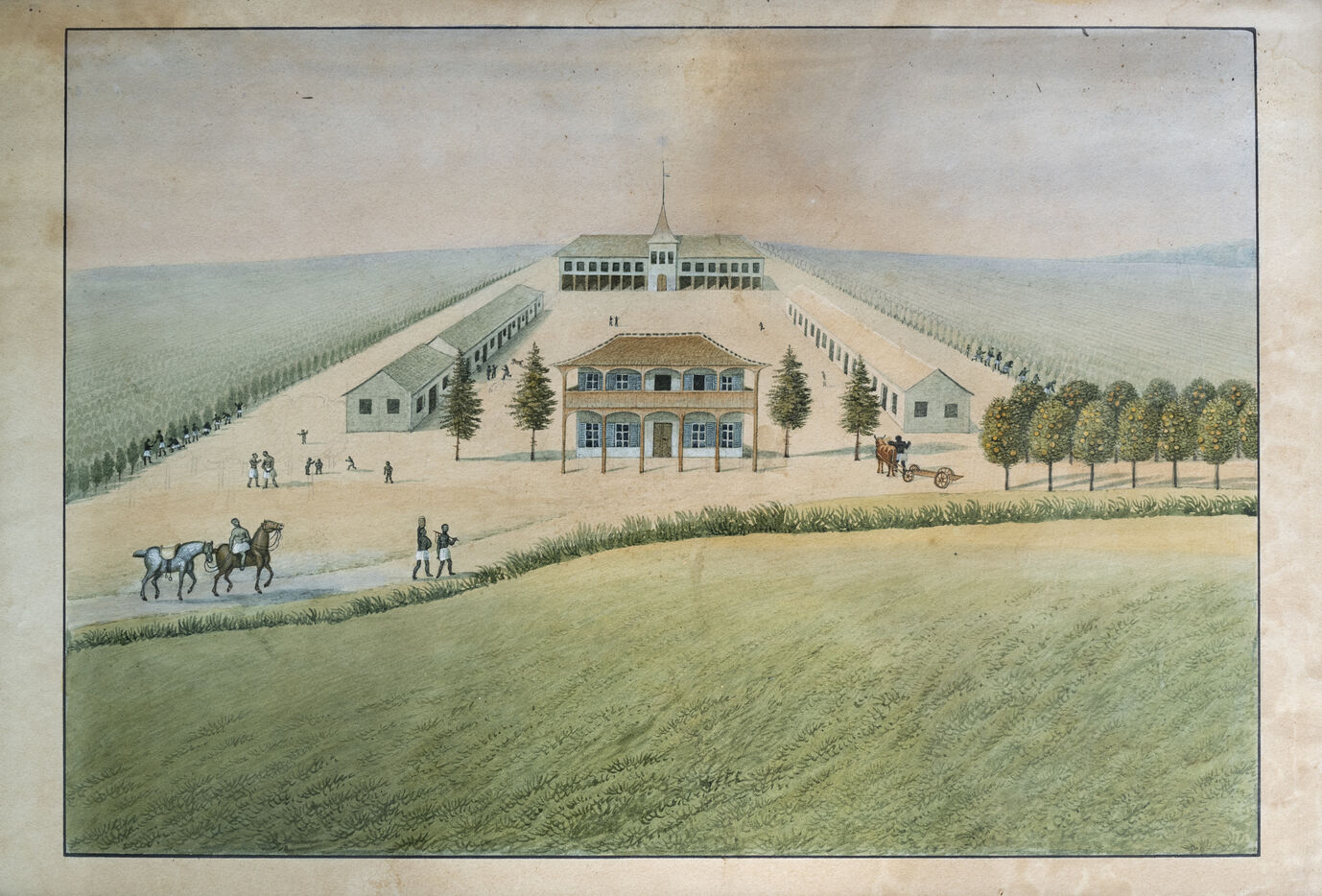

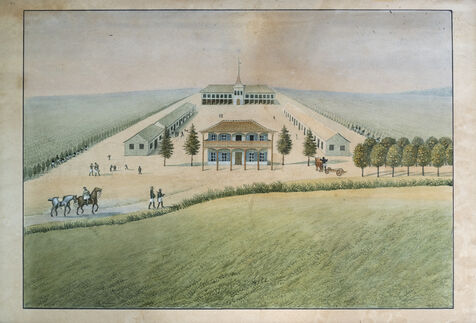

Ce travail explore les traces du passé et témoigne de la réalité de Helvécia et de sa population. La communauté villageoise doit son nom suisse à une plantation dont elle est issue, fondée au début du XIXème siècle par une poignée de colons suisses et allemands. Les immigrants ont développé une colonie qui va rapidement prospérer due à l’exploitation de milliers de personnes afrodescendantes réduites en esclavage pour y cultiver du café, permettant aux colons blancs d’amasser des richesses considérables. Avec le soutien du gouvernement suisse, la colonie va devenir l’un des plus importants exportateurs de café de l’Etat de Bahia jusqu’à l’abolition de l’esclavage au Brésil en 1888.

Fin 2022, Un livre sur le sujet été publié par Lars Müller Publishers, ainsi qu’une exposition de 350m2 présentée au Musée ethnographique de Genève (MEG), qui a attiré plus de 13'000 visiteurs. Puis fin 2024 une partie de ce projet a été présenté au Landesmuseum de Zürich, dans le cadre de l’exposition “KOLONIAL”, qui présenta, pour la première fois dans le musée national suisse, les liens entre la Suisse et le colonialisme.

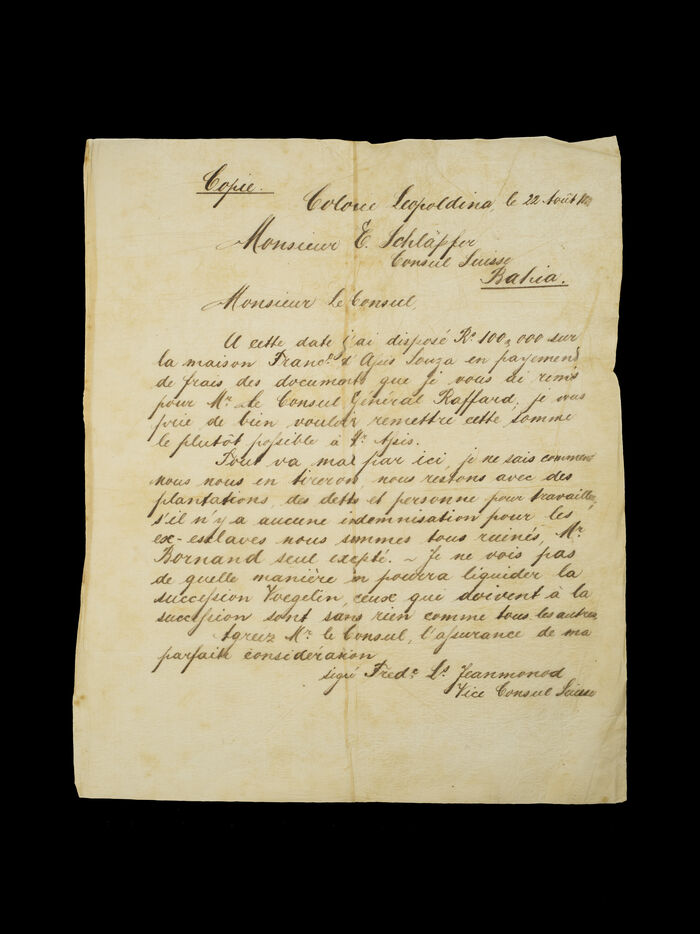

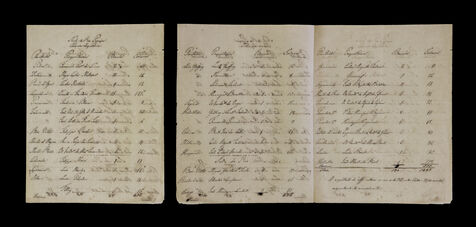

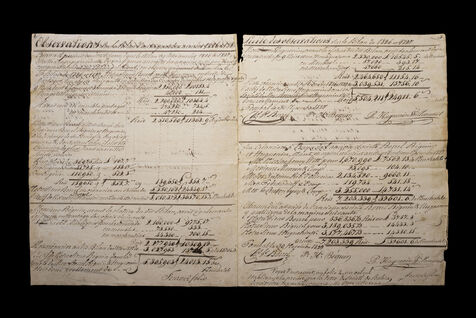

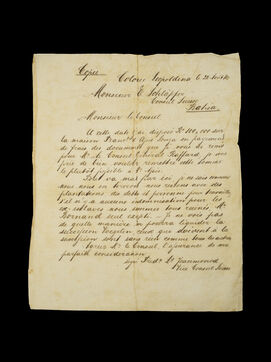

Il était important que ce sujet soit traité, tant pour les Suisses que pour les habitants de Helvécia qui, pour la plupart, n'avaient qu'une connaissance limitée de leur propre histoire. De plus, les fragiles traces du passé sont sur le point de disparaître. Dans le village, peu de choses sont faites pour préserver l'histoire, tant sur le plan matériel que pédagogique. En Suisse, quelques rares documents sont conservés dans les Archives fédérales et d’Etat, souvent tombés en poussière et en trop mauvais état pour être numérisés. Par chance certains de ces documents démontrant cette histoire, ont pu être photographiés et reproduits dans le livre.

En plus des photographies et des documents historiques, le livre est contextualisé avec des faits historiques et des aspects culturels par différents auteurs, Milena Machado Neves, journaliste ; Christian Doninelli, journaliste ; Shalini Randeria ; anthropologue sociale, rectrice de l'Université d'Europe centrale à Vienne depuis 2021 et ancienne rectrice de l'IHEID à Genève ; Rohit Jain, anthropologue sociale et chercheur associé à l'Université de Zurich ; Izabel Barros, historienne et activiste décolonialiste au Brésil et en Suisse ; Flávio dos Santos Gomes, historien spécialisé dans le thème de l'esclavage et professeur à l'Université fédérale de Rio de Janeiro.

article presse - Neue Zürcher Zeitung (allemand)

article presse - L'Illustré (français)

article presse - Arcinfo.ch (français)

"One Photo - One Story" - Leica Fotografie International (anglais)

Helvécia

Helvécia book was shortlisted for the Kraszna-Krausz 2023 Photography Book Award, and this story won the 2nd prize of the Swiss Press Photo Award 2023, in the category "Swiss Stories".

This work explores traces of the past and the reality of Helvécia and its people. The village community owes its Swiss name to a plantation from which it sprang, founded in the early 19th century by a handful of Swiss and German colonists. The immigrants developed a colony that rapidly prospered thanks to the exploitation of thousands of enslaved Afrodescendants to grow coffee, enabling the white colonists to amass considerable wealth. With the support of the Swiss government, the colony became one of Bahia's most important coffee exporters until the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888.

At the end of 2022, a book on the subject was published by Lars Müller Publishers, along with a 350m2 exhibition at the Musée ethnographique de Genève (MEG), which attracted over 13,000 visitors. Then, at the end of 2024, part of this project was presented at the Landesmuseum Zürich, as part of the “KOLONIAL” exhibition, which presented, for the first time in the Swiss national museum, the links between Switzerland and colonialism.

It was important to address this subject, both for the Swiss and for the people of Helvécia, most of whom had only a limited knowledge of their own history. What's more, the fragile traces of the past are on the verge of disappearing. In the village, little is being done to preserve history, either materially or educationally. In Switzerland, a handful of documents are preserved in federal and state archives, but these have often turned to dust and are in too poor a condition to be digitized. Fortunately, some of these documents have been photographed and reproduced in the book.

In addition to the photographs and historical documents, the book is contextualized with historical facts and cultural aspects by various authors, Milena Machado Neves, journalist; Christian Doninelli, journalist; Shalini Randeria; social anthropologist, Rector of the Central European University in Vienna since 2021 and former Rector of the IHEID in Geneva; Rohit Jain, social anthropologist and associate researcher at the University of Zurich; Izabel Barros, historian and decolonial activist in Brazil and Switzerland; Flávio dos Santos Gomes, historian specializing in slavery and professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung's press article (German)

L'Illustré' press article (French)

Arcinfo.ch press article (French)

Leica Fotografie International's "One Photo - One Story" (English)