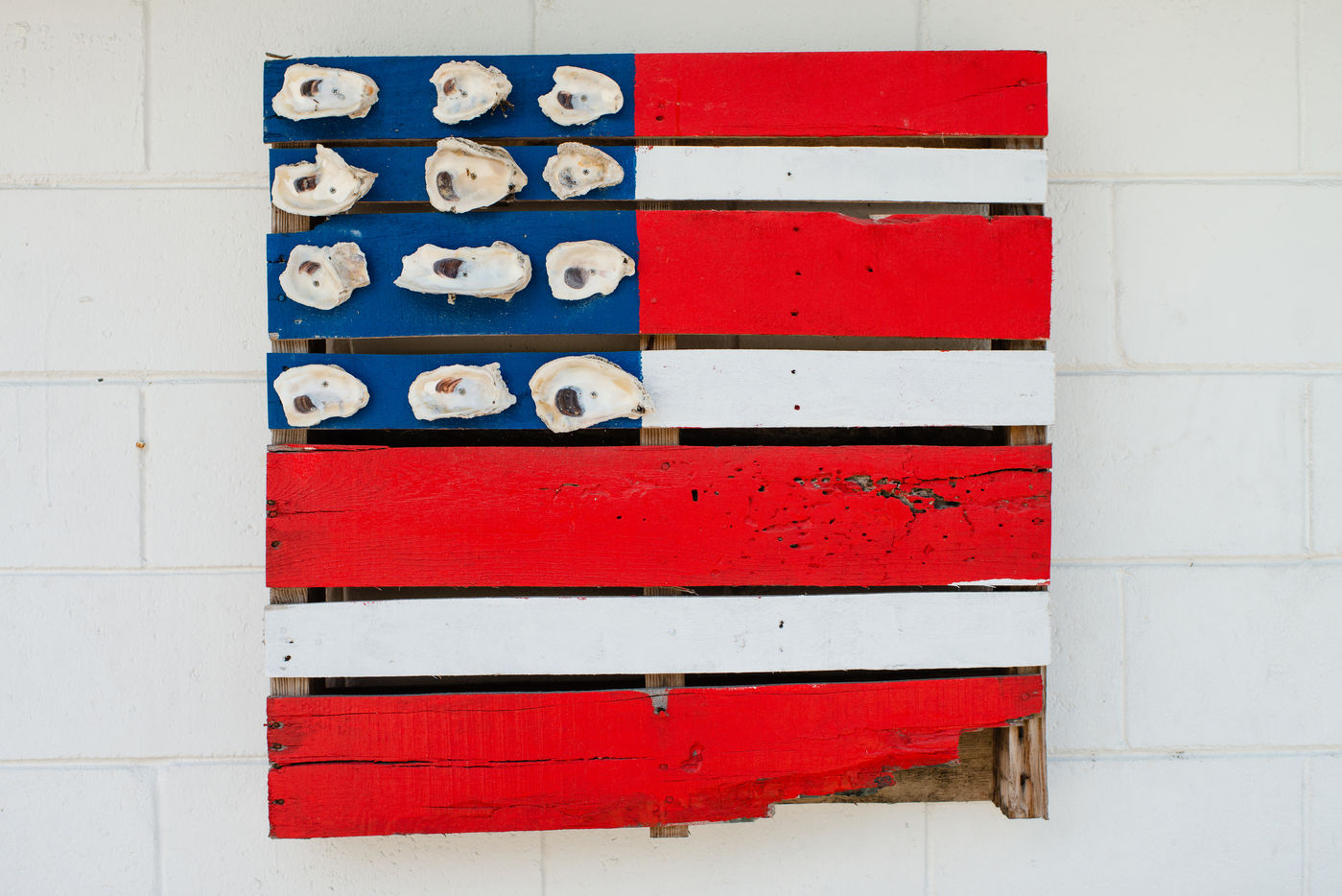

Les derniers huitriers sauvages

Autrefois numéro un des huitres aux Etats-Unis, représentant 10% de la production nationale, les récoltes de la Baie d'Apalachicola ne sont plus ce qu'elles étaient. Les huîtres ont besoin d'un mélange d'eau fraîche et d'eau salée pour se développer et c'est le plus salé que l'on ait vu la baie de son histoire. Il y a 10 ans, deux personnes pouvaient atteindre la limite de récolte avant le déjeuner. Une famille pouvait vivre de ce que la baie fournissait. Aujourd'hui, un ostreiculteur peut seulement travailler 4 jours par semaine et ramener 2 sacs par jour (23 kilos d'huître par sac) et même les meilleurs d'entre eux n'atteignent pas ce quota, s'ils travaillent légalement. Seuls les plus fervents et quelques nouveaux desespérés restent. La plupart des ostreiculteurs ont trouvé du travail dans les terres, dans la construction ou dans l'entretien de locations saisonnières des îles du coin comme Saint George ou Cape San Blas. Pour ceux qui n'ont pas réussi à faire la transition, l'alcool et la drogue servent d'échappatoire. Le seul espoir de l'industrie de l'ostreiculture repose sur l'aquaculture, ce qu'on appelle les huîtres d'élevage. Quelques entreprises nouvelles venues ont commencé à recolter avec des résultats positifs mais, avec des coûts initiaux très élevés, cette option n'est pas accessible à tous. Pendant que les locaux tentent de maintenir l'industrie en vie, la Court Suprême des Etats-Unis demandent plus de tests, prolongeant une année de bataille juridique, mais plus de recherche ne sera peut-être pas utile. Cela pourrait être la dernière année de récolte d'huîtres sauvages dans la baie d'Apalachicola.

The Last Wild Oystermen

Once the leader in US oysters, accounting for 10% of the nation's production, the harvest from the Apalachicola Bay is a shadow of its former self. Popular belief is water use upstream, specifically, the thirsty Atlanta metro area has reduced the once strong Apalachicola river to a trickle. Oysters need a mix of fresh and salt water to thrive, the bay is now more salt than any point in its history. Today an oysterman can only work 4 days a week bringing in two bags a day (50lbs of oysters per bag) and even the best don?t hit that limit, if they work legally. 10 years ago it was a max of 20 bags a person a day and a team of two could hit that and be home for lunch. You would see a husband and wife team, the husband tonging (collecting oysters off the bottom of the bay using two long rakes) and the wife culling (sorting the good from the bad) supporting a family off what the bay provides. Now only a few die-hards and desperate newcomers remain. Most of the former oystermen have found land jobs, construction or home cleaning in the nearby vacation rental communities of Saint George Island or Cape San Blas. For those who haven't made the transition, alcohol and drugs offer an escape. The one bright spot on the horizon for the oyster industry falls on aquaculture, known as farm-raised oysters. A few new upstart businesses have begun harvesting with positive results, but with high upfront costs, this option is not available to all. While residents try to keep the industry alive, the issue has become a legal one. Earlier this year the US Supreme Court ordered more testing, continuing a battle which has gone on for years, but more research may not matter. This may be the last year of wild harvest from the Apalachicola Bay.