Pour accéder à la série en entier, vous devez vous logger ou demander un compte Hans Lucas en cliquant ici.

C'était écrit

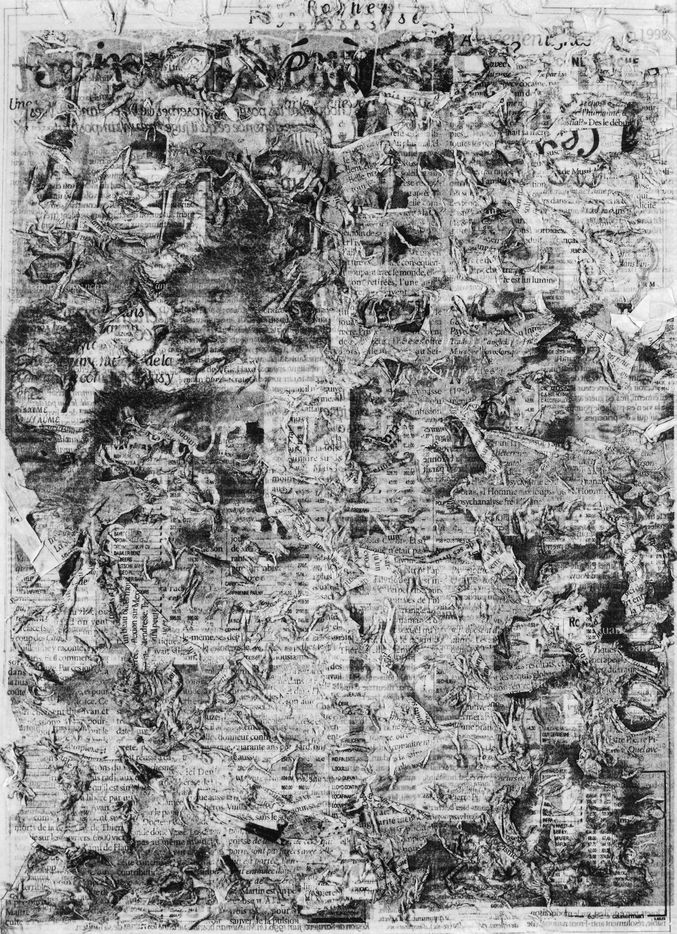

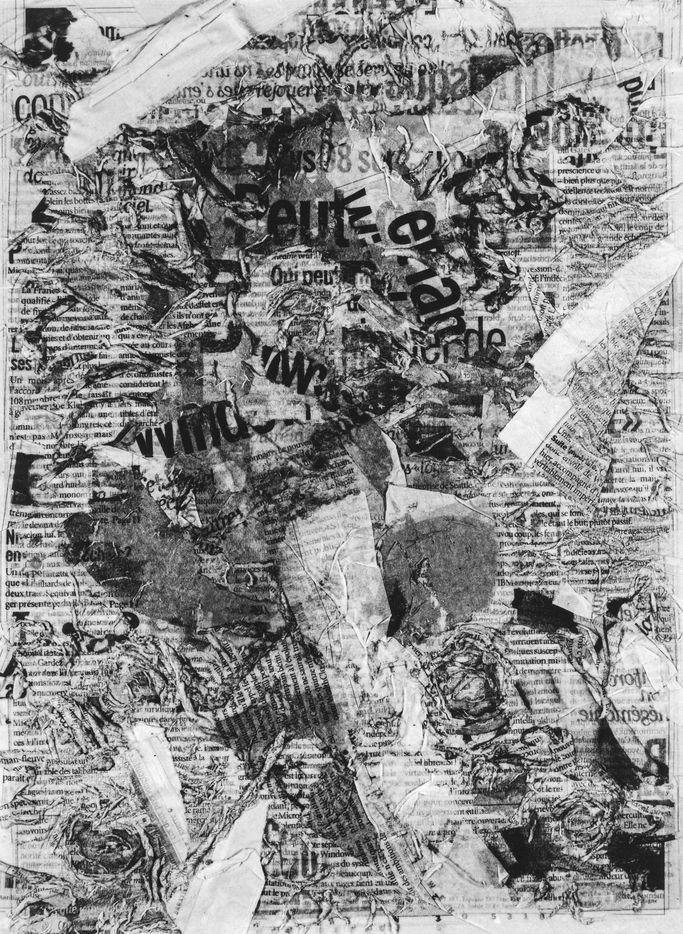

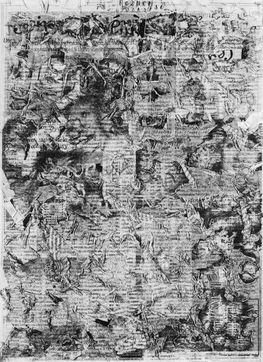

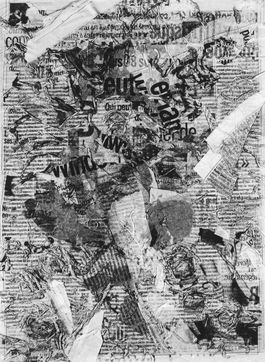

Les métamorphoses de l'archive : l'intimité du quotidien

La série

C'était écrit de Lionel Fourneaux est par certains aspects une sorte de parenthèse dans son travail, par d'autres, elle y occupe une place très nécessaire. Si, depuis longtemps, toute son oeuvre tourne autour de l'archi-mystère photographique qu'on peut formuler ainsi : comment toutes les choses photographiables du monde peuvent-elles tenir dans/sur l'extrême minceur des supports photographiques ? Comment y sont- elles retenues ? Ou, pour le dire encore autrement, comment se constitue l'espace secret où elles prennent tout à coup leur profondeur et leur séduction d'image ? Et si ces questions conduisent Lionel Fourneaux à des questionnements sur toutes les modalités, toutes les transformations et tous les supports de mémoire, soit pour les explorer, soit pour les excéder, il était inévitable qu'il s'en prenne un jour à cet objet très singulier qu¹est un

quotidien. Avec lui, tous les jours, on achète la mémoire du jour :

l'actualité comme on dit, c'est-à-dire, ce qu'il faudra retenir (ou oublier) demain de ce qui s'est passé hier. Tous les jours,

est présent sur le papier ce qui

s'est passé (ah ! le mystère du passé composé et du pronominal) hier. L'être des choses, dans le quotidien, est là parce qu'il est passé et qu'il y a été écrit.

Exactement comme l'image dans une image photographique.

Mais a-t-on bien pesé ce qu'il advient de ce qui

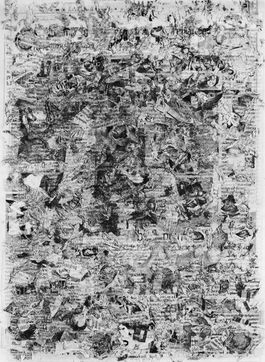

était écrit dans le journal, de ce qu'il en reste en nous (individuellement, collectivement), de ce qui s'y archive ? Lionel Fourneaux, prend cette question à bras le corps : trempe le journal assez longtemps pour quasiment le ramener à son état antérieur de pâte à papier, puis le ré-étale avec ce qui était écrit dessus et qui y est maintenant incorporé. L'écrit est devenu au passage une matière première. Vous voyez le résultat. Pourquoi se met-on à penser à une gravure à l'eau-forte, un vieux Dürer, par exemple ? Toute cette dispersion aléatoire de ce qui était écrit, la veille à peine, nouée à la matière du support, nous ramène donc à une vieille et mélancolique technique de reproduction ? N'est-ce pas cela que cette série indique : l'espace de l'image, n'est-ce pas ce rappel à du très ancien qui remonte d'un magma de mémoire : finalement, n?est-ce pas cela, la réelle intimité du

quotidien ?

Bernard Cier, philosophe et écrivain

C'était écrit

The metamorphoses of the archive: the intimacy of everyday life

The series C'était écrit by Lionel Fourneaux is in some respects a kind of parenthesis in his work, in other respects, it occupies a very necessary place in it. If, for a long time, all his work revolves around the photographic arch-mystery that can be formulated as follows: how can all the photographable things in the world fit into/on the extreme thinness of photographic supports? How are they retained there? Or, to put it another way, how is the secret space constituted where they suddenly take on their depth and seduction of image? And if these questions lead Lionel Fourneaux to question all the modalities, all the transformations and all the supports of memory, either to explore them, or to exceed them, it was inevitable that he would one day take on this very singular object that is a daily newspaper. With him, every day, we buy the memory of the day: the news as we say, that is to say, what we will have to remember (or forget) tomorrow of what happened yesterday. Every day, is present on the paper what happened yesterday (ah! the mystery of the compound past tense and the pronoun). The being of the things, in the daily life, is there because it is past and that it was written there.

Exactly like the image in a photographic picture.

But have we really weighed what happens to what was written in the newspaper, what remains in us (individually, collectively), what is archived there? Lionel Fourneaux, takes this question in hand: soaks the newspaper long enough to almost bring it back to its former state of paper pulp, then re-spreads it with what was written on it and which is now incorporated into it. The writing has become a raw material in the process. You see the result. Why does one start thinking about an etching, an old Dürer, for example? All this random dispersion of what was written, the day before, tied to the material of the support, brings us back to an old and melancholic technique of reproduction? Isn't that what this series indicates: the space of the image, isn't it this reminder of the very old that rises from a magma of memory: finally, isn't that the real intimacy of the everyday?

Bernard Cier, philosopher and writer