Pilote maritime du port de Saint Malo

Il ne fait pas tout à fait jour sur Saint Malo, en ce venteux matin de novembre. La météo n'est pas des plus mauvaise mais les éléments se font sentir dans l'air chargé d'iode, ce qui indique que cela doit brasser pas mal en mer.

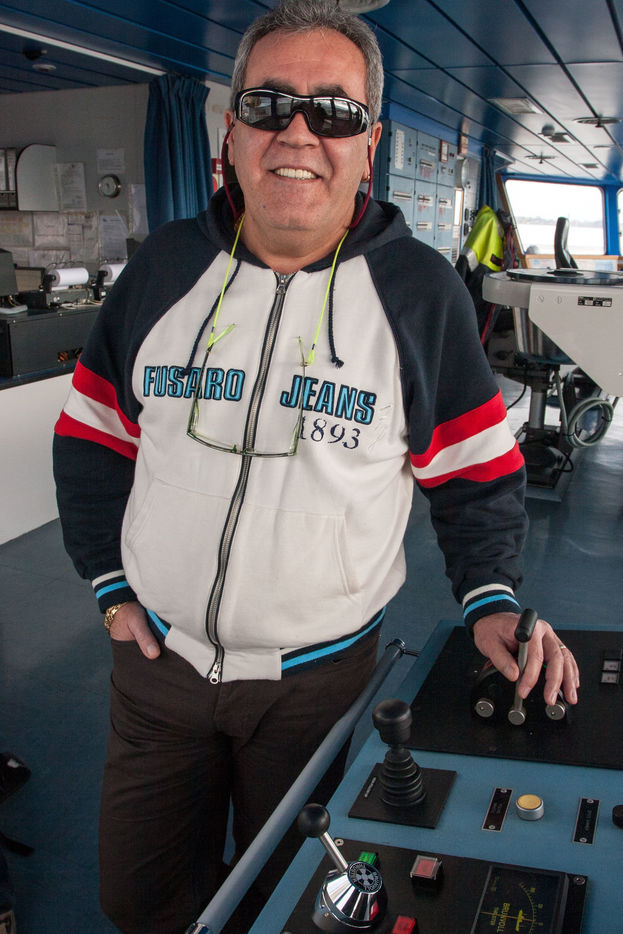

C'est dans l'enceinte du fort de la Naye que se trouvent les locaux des pilotes marins du port de Saint Malo. On frappe à la porte et c'est Eric Geille qui nous accueille, assis à son bureau où il finit de prendre les dernières informations concernant l'arrivée dans la baie du chimiquier, le « Ievoli sprint » qui vient livré 400 000 tonnes d'acide phosphorique.

C'est l'un des 350 bateaux de plus de 40 mètres de plaisance ou de commerce qui durant l'année doivent impérativement faire appel au savoir-faire de Eric et de ses collègues.

Eric est l'un des trois pilotes de la station. Natif du pays, il connaît tous les dangers de la baie, les cailloux mais aussi les courants qui subissent l'influence du barrage de la Rance, tout proche. Il y aussi les vents qui poussent les navires qui sont hauts, ou trop légers car vides. C'est sans compté avec le marnage qui peut varier de trois centimètre en dix minutes et de dix mètre en une heure.

« Si il y a bien un endroit où le pilote est nécessaire, c'est ici » nous confie Eric.

Le plus important rajoute-t-il, c'est sa capacité à créer une relation de confiance avec le capitaine :

« Si un commandant nous dit qu'il a un problème, on est censé l'avoir vécu pour savoir comment réagir. Je préfère avoir un bateau compliqué avec un capitaine qui nous fait confiance, que l'inverse. La première des choses, c'est l'humain, au point que parfois, de nuit, à la passerelle, on échange dans l'obscurité sans même se voir ... »

Il est vrai qu'on n'arrête pas les dizaines de milliers de tonnes d'un navire, même à deux noeuds. C'est là toute la subtilité du métier : «

Il ne peut y avoir de routine. Chaque bateau est problème à lui seul. Et même s'il est déjà venu car aussi bien l'équipage, la météo, la marée, le chargement sont différents à chaque fois. »

«

C'est un métier où il faut mouiller la chemise. Et ce n'est que du plaisir » conclut Eric Geille.

The maritime pilot of the port of Saint Malo

It is not quite light on Saint Malo on this windy November morning. The weather is not bad but the elements are felt in the iodine-laden air which indicates that it must be brewing quite a bit at sea.

It is in the enclosure of the Fort de la Naye that the premises of the marine pilots of the port of Saint Malo are located. We knock at the door and it is Eric Geille who welcomes us, sitting at his desk where he finishes taking the last information concerning the arrival in the bay of the chemical tanker, the "

Ievoli sprint" which has just delivered 400 000 tons of phosphoric acid.

It is one of the 350 boats of more than 40 metres in length, both pleasure and commercial, which during the year must imperatively call upon the know-how of Eric and his colleagues.

Eric is one of the three pilots of the station. A native of the country, he knows all the dangers of the bay, the rocks but also the currents which are influenced by the nearby Rance dam. There are also the winds which push the ships which are high, or too light because empty. The tidal range can vary from three centimetres in ten minutes to ten metres in an hour.

"If there is one place where the pilot is needed, it is here." Eric confides to us.

The most important thing, he adds, is his ability to create a relationship of trust with the captain:

"If a commander tells us he has a problem, we are supposed to have experienced it to know how to react. I'd rather have a complicated boat with a captain who trusts us than the other way round. The first thing is the human element, to the point that sometimes, at night, on the bridge, we exchange in the dark without even seeing each other...".

It is true that you can't stop a ship's tens of thousands of tonnes, even at two knots. This is the subtlety of the job: "there can be no routine. Each ship is a problem in itself. And even if it has been there before, the crew, the weather, the tide, the load are different every time. »

"It's a job where you have to wet the shirt. And it's just fun" , concludes Eric Geille.