Occupied breathing

« Il n'y a pas une occupation du terrain et une indépendance des personnes. C'est le pays global, son histoire, sa pulsation quotidienne qui sont contestés, défigurés, dans l'espoir d'un définitif anéantissement. Dans ces conditions, la respiration de l'individu est une respiration observée, occupée. C'est une respiration de combat. » Frantz Fanon, L'an V de la révolution algérienne, 1959.

Situé entre le Maroc, la Mauritanie, et l'Algérie, le Sahara Occidental reste le dernier territoire à décoloniser sur le continent africain.

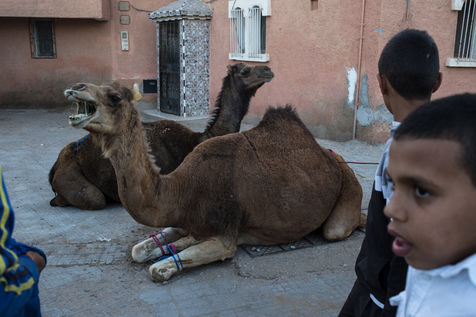

Avant même le départ des espagnols, la brutale invasion par le Maroc en 1975 a expulsé la population sahraouie hors de son territoire, vers des camps de réfugiés dans le désert algérien. Les sahraouis restés sur le territoire occupé sont minoritaires. Séparé du reste de leur peuple par un mur de séparation long de 2700km, ils subissent la répression et la discrimination.

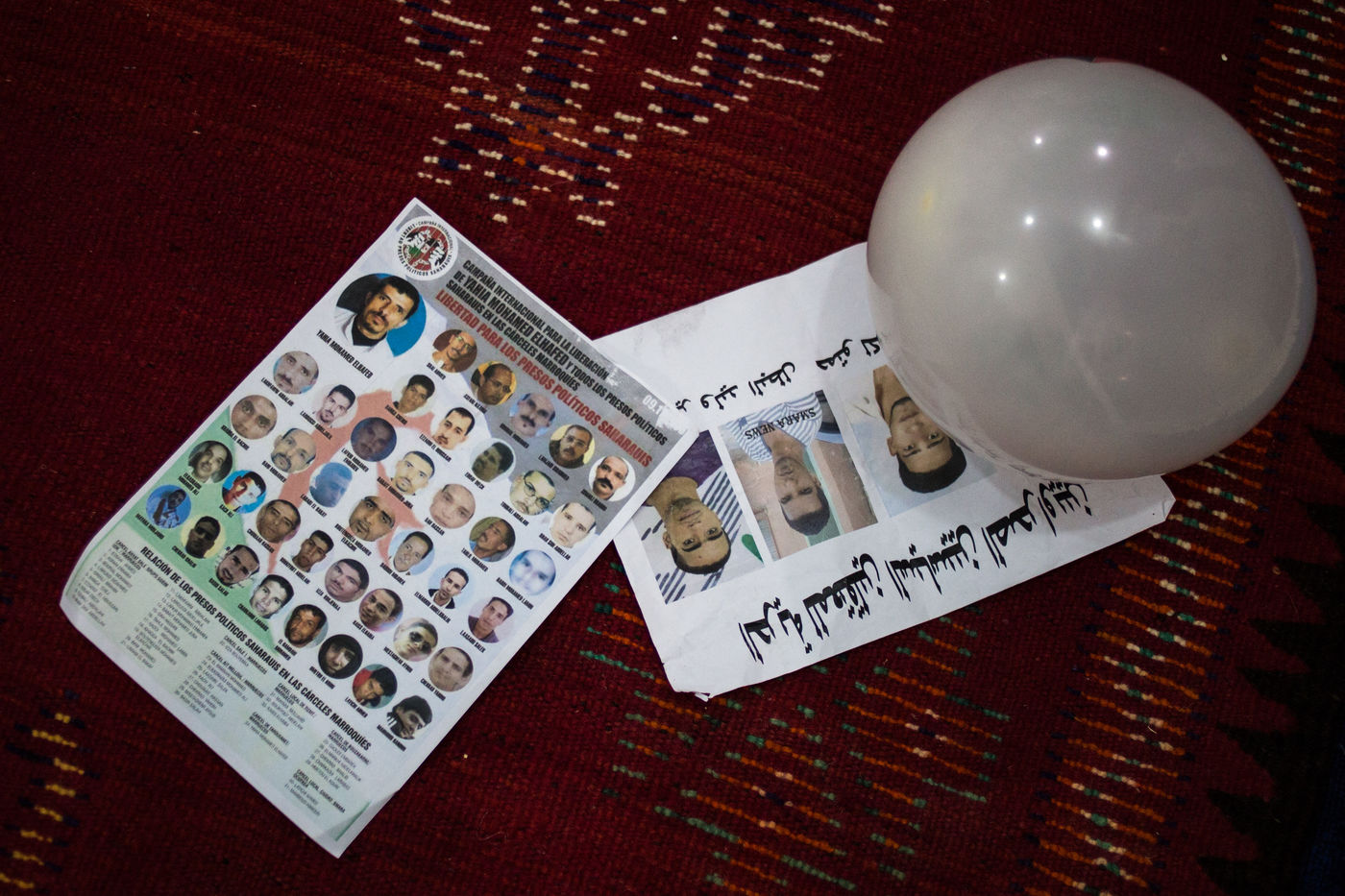

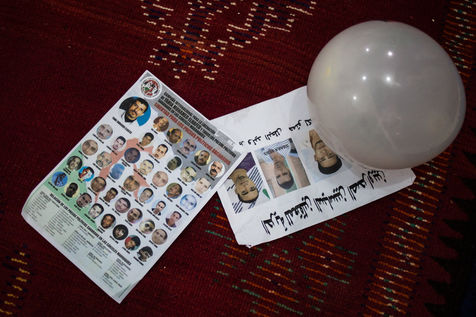

Le nomadisme étant interdit par la nouvelle force occupante, la ville va dès lors imposer un cadre socio-politique qui tend vers une assimilation forcée, et un contrôle des corps colonisés et des résistances basé sur le tout-répressif : emprisonnements, disparitions, tortures, harcèlements, etc. Pour eux ce désert est une prison à ciel ouvert, qui se matérialise par leurs impuissances à faire respecter leurs droits sur ce territoire perdu. La colonisation place le colonisé hors du temps, hors de l'espace, dans un rapport dominant-dominé.

Le cessez-le-feu signé entre le Maroc et le Front Polisario (l'armée de la République Arabe Sahraouie Démocratique) en 1991, mandate l'ONU de surveiller le cessez-le-feu, et d'organiser le retour des réfugiés, le référendum d'autodétermination, et la réduction des troupes marocaines sur le territoire.

Aujourd'hui rien n'a évolué, si ce n'est l'emprise coloniale, dans un contexte international qui, de facto, semble considérer comme acceptable le statu quo imposé par cette occupation, au mépris du Droit International Humanitaire.

Le processus d'urbanisation et les campagnes de peuplement intensifs sont des mécanismes de déculturation colonial du peuple sahraoui qui ambitionnent d'atteindre un point de non-retour : la "marocanité" irréversible du Sahara Occidental.

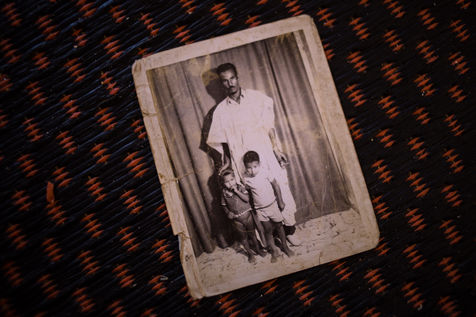

Cependant, malgré les investissements colossaux sur ce territoire, le Maroc se heurte aux résistances. L'identité sahraouie repose sur le combat pour l'autodétermination. Dès 1973, la résistance a fédéré les tribus en peuple, et le dénominateur identitaire n'est plus le lien du sang, mais l'appartenance à un même territoire.

Divers moyens d'ordre politique, économique, social, culturel, linguistique, permettent de s'extirper du contrôle colonial. Préserver ses différences culturelles constitue un rempart à l'intégration marocaine qui permet d'assurer la continuité de la lutte jusqu'à l'autodétermination.

L'affirmation de l'identité sociopolitique et culturelle des Sahraouis les met face à un État qu'ils contestent mais au sein duquel ils évoluent malgré eux. Vivre sous occupation est une histoire d'accommodation, en même temps que de résistance. C'est une respiration de combat contre l'aliéniation, pour la liberté.

« Quand nous sommes tous dispersés, qu'il nous semble être devenus des étrangers sur notre propre terre, quand notre identité nationale, nos traditions, nos conceptions du monde et nos droits individuels sont violés à chaque instant, que pouvons-nous faire pour continuer à prendre des initiatives au niveau politique, économique, social ou dans notre propre vie ? Nous avons à chaque instant la sensation douloureuse d'avoir perdu notre vie, nos familles et nos biens. Tout nous apparaît en permanence comme une menace, nous avons perdu tout sentiment de sécurité. Mais que pouvons-nous faire ? Baisser la tête ou clamer la vérité jusqu'à ce que tout le monde nous entende ? » Brahim Dahane, militant sahraoui des droits de l'Homme, victime de disparition forcée sous Hassan II et d'emprisonnement sous Mohamed VI.

Occupied breathing

"There is no occupation of territory, on the one hand, and independence of persons on the other. It is the country as a whole, its history, its daily pulsation that are contested, disfigured, in the hope of a final destruction. Under these conditions, the individual's breathing is an observed, an occupied breathing. It is a combat breathing". Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism, 1959.

Located between Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria, Western Sahara remains the last territory to be decolonized on the African continent.

Even before the departure of the Spaniards, the brutal invasion by Morocco in 1975 expelled the Sahrawi population out of its territory, to refugee camps in the Algerian desert. Only a minority of Sahrawis remained in the occupied territory. Separated from the rest of their people by a 2700km long separation wall, they suffer from repression and discrimination.

Nomadism being banned by the new occupying force, the city therefore imposes a socio-political framework that tends towards forced assimilation, and a control of colonized bodies and resistances based on the all-repressive : imprisonment, disappearance, torture, harassment, etc. For them this desert is an open prison, which is materialized by their inability to enforce their rights in this lost territory. Colonization places the colonized out of time, out of space, into a dominant-dominated relationship.

The ceasefire signed between Morocco and the Polisario Front (the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic army) in 1991, mandates the UN to monitor the cease-fire, and to organize the return of the refugees, the referendum of self-determination, and the reduction of the Moroccan troops on the territory.

Today nothing has changed, apart from the colonial domination, in an international context which, de facto, seems to consider as acceptable the status quo imposed by this occupation, in defiance of International Humanitarian Law.

The process of urbanization and intensive settlement campaigns are mechanisms of colonial deculturation of the Sahrawi people, in order to reach a point of no return : the irreversible "moroccanity" of Western Sahara.

However, despite huge investments in this territory, Morocco is facing resistance. Sahrawi identity is based on the struggle for self-determination. Since 1973, the resistance has federated the tribes into people, and the common identity denominator is no longer the link of blood, but the sense of belonging to a territory.

Various political, economic, social, cultural and linguistic means make it possible to brake free from colonial control. Preserving its cultural differences is a bulwark against Moroccan integration, it ensures the continuity of the struggle for self-determination.

The affirmation of the socio-political and cultural identity of the Sahrawis puts them face to face with a State that they contest but within which they evolve in spite of themselves. Living under occupation is both a story of accommodation, and resistance. It is a combat breathing against alienation, for freedom.

"When we are all scattered, that we seem to have become strangers on our own land, when our national identity, our traditions, our conceptions of the world and our individual rights are violated at every moment, what can we do to continue to take political, economic, or social initiatives in our own lives ? At every moment we have the painful feeling of having lost our lives, our families and our property. Everything always seems like a threat, we have lost all sense of security. But what can we do? Lower your head or claim the truth until everyone hears you? Brahim Dahane, Sahrawi activist for human rights, victim of enforced disappearance under Hassan II and imprisonment under Mohamed VI.